Hello World!

This is the first blog in a series of blogs on machine learning techniques. Machine Learning is the new cool buzzword and for good reason. The impact is immense and to the untrained eye; it is magic. But with this series of blogs, hopefully you’ll cross over to the other side and be the one doing all the magic stuff!

First cool word - Regression

Alright, so we begin our journey in this rabbit hole called Machine Learning (ML) with something simple yet powerful, a technique called Regression. This is really the "Hello World" equivalent of machine learning. Regression is not as complicated as it sounds (sounds cool though). Basically regression is about predictions. It is a technique to study some data, learn/estimate the underlying pattern and make predictions based on that.

We can perform classification where we “predict” the category or (class or labels in ML speak) for some given input. So for example if we wish to develop a spam filter, we might have categories to classify an e-mail into “spam” or “not spam”. Another type of prediction is about predicting an actual value. Say you’re trying to sell/buy a house, then based on the past prices you can predict the prices at several points in future and this can help you take a more informed decision. All of this can be done with the so called "Hello World" of Machine Learning!

Before diving deeper, here are some more cool words used with regression that the community likes and you’ll often see in ML literature. When we try to predict something, we are studying some data first. This data basically tells us about things that may or may not be relevant in making our predictions. So in case of our house prices, the data can be about the size of the house, number of rooms, etc. These are the “features” of the house. These features help us make our “prediction” and our often referred to as features or predictor variables. Now our prediction depends on the features in our dataset and so it is called the dependent variable. So in a way, our predictor variables our independent variables. So our inputs are called feature / predictor / independent variables while our output is called the dependent variable. In this post, we will be discussing Logistic Regression, a popular algorithm used mostly for classification tasks.

Even cooler word - Logistic Regression

Logistic regression is all about predicting a class for your input data. Given an input, you determine which class it belongs to. The simplest examples deal with just two classes, a binary classification task. This include tasks like spam or not spam, happy tweet vs a depressing tweet and so on. Of course you can have a classifier choose from more than two classes, in which case it is called Multinomial Logistic Regression (another cool word to add in your ML dictionary).

Alright, so lets say you wish to build your own spam classifier. Now the first task is to select the features. These features are something that are used to determine if an email is a spam or not. For the sake of simplicity, let us assume that the features are feature 1 and feature 2 denoted by $x_1$ and $x_2$. Let’s say we decide upon the following linear function

$$y = a x_1 + b x_2$$

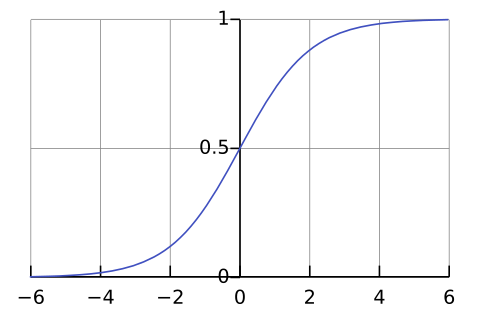

Since we are trying to predict if the email is a spam or not, we are interested in the probability of it being a spam. So we pass the value of our linear function through something called a sigmoid function. This is because sigmoid function always returns a value between 0 and 1. This range is similar to what we need for a probability. The sigmoid function is given by the following equation.

$$σ(x) = 1 ⁄ (1 + e^{-x})$$

And this is what sigmoid looks like when plotted on a graph:

Image Courtesy: Qef at Wikimedia

As you can see, the output ranges from 0 to 1 on the negative and positive ends respectively, and is 0.5 when the input is zero. Hence we can provide it with any number and get a number between 0 and 1 back. So our spam filtering function will look like:

def isSpam(y):

probability = sigmoid(y)

return probability > 0.5

Now the goal here is to learn the parameters a and b such that after applying the sigmoid function we get a number greather than 0.5 for spam mails. We already have the data from which we can learn, the question is how to learn the parameters from that data. Well, we guess the values initially and see how it works for the training data. And then we adjust these values by comparing our predictions with actual answers. In order to accomplish this, we need our next cool word, loss function.

Loss Function

So what a loss function does is, well; tells you your loss. This function will tell us how far we are from the correct answer. It is our feedback system which will provide us with hints about how we should adjust our learning parameters. Think of it as a little guide whose job is to point in the right direction. So for a problem like this, a popular loss function is already available, The Cross Entropy loss function. Before sticking the equation in your face I would digress here for a moment to explain what it really is and why it is useful.

Entropy

Let’s say that you want to send a large message to your friend but you get charged for every bit you send (you kinda do). Now one way to minimize the cost would be to send the message with as little bits as possible. We do that by picking short binary representations for most frequent alphabets and larger ones for the relatively rare ones. This way we can bring the cost down. The minimum number of bits you will need is given by $log(1/p_x)$ where p is the probability of seeing symbol x. So if letter $x_1$ occurs about 64 times more than letter $x_2$, then

$$ \begin{eqnarray} bits\_x1 &=& log (1 / 64 * p(x_2)) \nonumber \\\ &=& log(1/64) + log(1/p(x_2)) \\\ &=& -6 + bits\_x2 \\\ \end{eqnarray} $$

So you would use about 6 bits less for letter $x_1$ than for $x_2$. For our entire message, the entropy will be the expected number of bits we used for our encoding. Expectation means the average value seen over a series of experiments. For a experiment of rolling dice, the expected value is 3.5 since we see all 6 values equal number of times (equal probability). Mathematically, you get expectation by summing up the products of value with their respective probabilities. You can check that that will give 3.5 for a fair dice. Below is a one liner to calculate entropy.

entropy = sum([x*log(1/x) for x in probability_of_symbols]

Here we used our knowledge of data distribution to encode symbols. Now suppose we didn’t know the distribution, we would be encoding based on a guessed distribution H’ then. This will always be greater than or equal to the actual entropy H since that is the minimum. Now if our guessed distribution uses the probability function p’(x) instead of the correct one p(x), then cross entropy H(p, p’) will be the number of bits we will need with this new distribution given as:

$$H(p,p’) = ∑ p\ log(1/p’) = − ∑ p\ log (p’)$$

So going back to our cross entropy loss, we are detecting probabilities of an email being a spam. Lets say y is the actual probability of it being a spam and a is the one our algorithm detects. We have only two possible inputs, a spam email (prob: p) and a non-spam email (prob: 1-p). Hence our cross entropy summation will expand to just two terms;

cross_entropy = - y * log(a) - (1 - y) * log(1 - a)

Interesting things to note:

- The input to log is always between 0 and 1, hence output is negative, and with the negative signs outside, our cross entropy will always be positive.

- If y is 0 and a is close to 0; or if y is 1 and a is close to 1, our cross entropy is 0 ($∵ log(1) = 0$ and while $log(0)$ is undefined, its partner becomes 0).

- If y is 0 and a is close to 1; or if y is 1 and a is close to 0, our cross entropy starts growing high.

All those features are what we desire from a loss function: it stays positive, returns 0 when we are right and higher values as we go more wrong. Hence over our training data with n examples, our loss over the entire dataset, the cross entropy loss will be average of the cross entropy over all training examples, where we calculate cross entropy for each based on the previous formula. $$H(p,p’) = -1/n ∑ (cross\_entropies)$$

Okay, like any sane person we are trying to minimize the loss function and that is how we measure the effectiveness of our learning parameters. In order to actually get our parameters a and b from this loss function, we have two ways:

- Solve the problem of $minarg(H(p,p’))$ w.r.t. to $a$ and $b$. Sparing the equations, intuitively our loss function can be thought of as a curved surface in 3D where two of the dimensions are our inputs and the third one is our loss function. We are then trying to find the lowest point (minimum loss) on the surface. At the lowest point, the derivative of the curve will be zero and hence you can solve for that. But that quickly gets out of hand for more number of parameters and hard to differentiate functions.

- A technique called Gradient Descent. This technique merits a blog of its own (maybe in future) but here’s a quick overview. At a point on the curve, you look around to see which direction has the steepest slope downwards (since we are trying to minimize loss) and then you take a small step in that direction. And then you repeat the process again till you have reached the minimal point.

Of course these techniques face the risk of being stuck in a local minima, a point where it seems that this is the lowest point when you look around but is not the globally lowest point. It is like falling in a pit and thinking if you’ve reached the center of the earth. Anyways, those issues are a thing of their own, but for now don’t worry about those and trust that these techniques work (they do!).